media centre

Keep up to date with the latest news, comment and insight from SMMT, covering all key UK automotive industry issues, developments and trends, including market and manufacturing performance across every sector.

News

FILTER search:

Select year

Select year

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1997

1995

1994

1993

1992

1991

1990

1989

1988

1987

1985

1984

1983

1982

1981

1980

1979

1978

1977

Select month

Select month

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

News

Trade

SMMT statement on UK-US trade deal kicking into gear

30 Jun 2025

News

CEO Update

A landmark week for UK industry

27 Jun 2025

News

Car

Car manufacturing

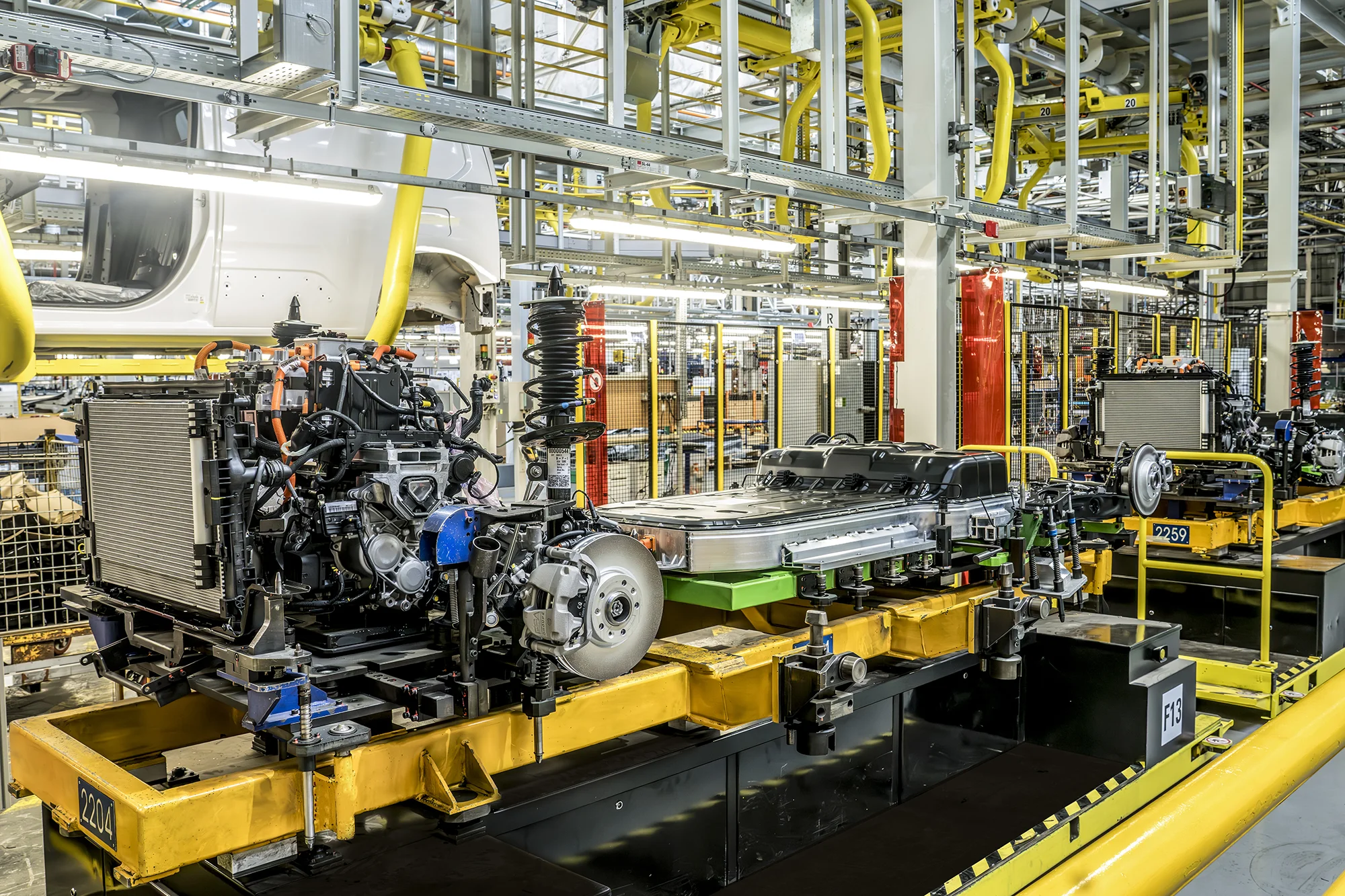

UK vehicle production constraints continue in May

27 Jun 2025

News

Pre registrations

May 2025 new car pre-registration figures

26 Jun 2025

News

Electric vehicle

SMMT response to Government’s Trade Strategy

26 Jun 2025

News

Membership

New Members – June

25 Jun 2025

News

Car

Industrial Strategy can be springboard for UK auto success

24 Jun 2025

Reports

Commercial Vehicle

Competitive Edge: Driving Long-Term UK Automotive Growth

24 Jun 2025

News

Electric vehicle